The Reading Room, Beadnell

20/06/2016 | Katrina Porteous (Local Historian)

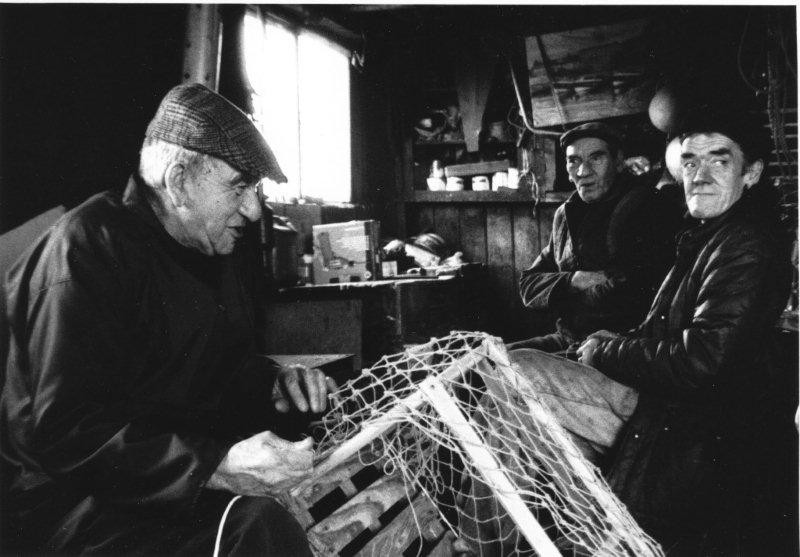

In February 1856 Mr W. Brown, a surgeon from North Sunderland Seahouses, visited Beadnell to deliver the first of a series of science lectures intended ‘to raise our thoughts from earth to heaven’.[i] About 40 years later, in January 1897, professional nurses were brought to Beadnell, to care for fever victims housed in a temporary hospital. ‘Many of the cases,’ a newspaper reported, ‘were of a very severe character, but only one person, a young woman, succumbed to its ravages.’[ii] Nearly 100 years later, in 1992, fisherman John Douglas sat, as he often did in winter-time, hammering a wedge into a cane bow through the base of a wooden ‘creeve’ (lobster pot), and recalled the story of his father and grandfather’s lucky escape from a nearly-fatal blizzard in 1894, in the coble Jane Douglas.[iii]

These three snapshots, separated by almost a century and a half, have one thing in common. They are all associated with, and probably all took place within, a simple wooden hut, familiar to Beadnell’s inhabitants from its prominent roadside position near the entrance to Harbour Road, and known to older Beadnell residents as ‘the Reading Room.’

The hut was once one of many ‘black huts’ in the village. It stood in a little archipelago of huts, on the grassy bank close to Beadnell Haven, where, until relatively recent times, fishing cobles were drawn up on the sand. The path which led from it to the sea was paved with broken mussel and limpet shells, bait from innumerable generations of long lines. Although it was built to serve the whole community – or at least the male half – from the beginning, its position at the Haven associated it with the fishing community, in particular with Fisher Square, a nearby structure of 11 stone cottages arranged around a central courtyard, built in 1777 by John Wood, to house Beadnell’s fishing families. The Square remained important to the fishing community until it was demolished in 1939.[iv]

The date of the Reading Room is not known. A Durham University thesis of 1993 dates ‘The Beadnell News Room’ to 1886, about the same time as Craster Memorial Hall Reading Room.[v] There is no evidence that ‘the members of the Beadnell Reading Room’ who attended Mr Brown’s uplifting lectures in 1856 met in that hut; but the likelihood is that they did. The fishermen’s story-telling tradition was reliable throughout their father’s memories, which stretched back to the 1880s, and they assumed that the Reading Room had existed before that, in their grandfather’s time. The historical development of the Reading Room movement also suggests a mid-19th century date.

It is not known whose idea it was to provide a Reading Room for the village, who paid for it, or who built it; but again some clues exist. The mid-19th century Reading Room movement came about as part of a temperance drive to keep working men – particularly miners – out of taverns and ale-houses. The Northern Association of Mechanics’ Institutes, whose President in the early 1850s was Sir George Grey of Howick, succeeded in 1858 by the Duke of Northumberland, included, in 1853, 28 institutions. By 1858, there were 84.[vi] The first reference to North Sunderland Reading Room, which occupied part of the Lord Crewe’s property in what is now the Bamburgh Castle Hotel, dates from that year.[vii] The Vice Chair of the Association’s committee at the time, Dr Robert Embleton, lived in Beadnell. There is no evidence that Beadnell Reading Room was at that time part of the Northern Association of Mechanics’ Institutes; indeed, evidence suggests that it joined much later;[viii] but it would seem likely that Dr Embleton was at least involved in setting the idea in motion.

The leading landowner in Beadnell at this time was John Wood’s son, Thomas Wood Craster. He owned Fisher Square and the land at the Haven. It is not known whether he was a member of the Association of Mechanics’ Institutes, but he would certainly have known people, like Dr Embleton, Sir George Grey and the Duke of Northumberland, who were committee members and important subscribers, and he might well have provided financial support for the building of the Reading Room. Another likely subscriber was local colliery owner Richard Taylor of Beadnell House. The colliery and adjoining limekilns and quarry were active in the 1850s,[ix] and would have added to the perceived need to provide an alternative to the ale-house.

Further along Harbour Road, next to the site of old Windmill Steads, stands another, similar, hut of comparable age to the Reading Room. Known as ‘Aa’d Weir’s hut’, this belonged in the late 19th century to the Fawcus fishing family. In common with many Beadnell black huts, it was used as occasional accommodation by the family, who moved out of their house during summer to let it to visitors for additional income.[x] Like Fisher Square, Windmill Steads belonged to Thomas Wood Craster. It is likely that whoever built the Reading Room also constructed Aa’d Weir’s hut. The joiner in Beadnell in 1855 was George Summers, father and grandfather to a dynasty of joiners and village postmasters. Again, there is no evidence that he built either hut, but he would be the most obvious contender.[xi]

Whatever its exact date and provenance, it is clear that for much of the second half of the 19th century the Reading Room provided a place for Beadnell’s working men to meet and relax. The hut housed a billiard table, and subscribed to newspapers. If it did have any association with the Mechanics’ Institute, it could have subscribed to its ‘itinerating library’ of improving volumes. The hut was originally heated by a wood-burning stove. Inside, it was finely wainscotted and wallpapered. Scraps of wallpaper from its original incarnation, heavily-patterned, smoke-stained and lined with newspaper so friable it turned to dust, yielded just enough print to date it to August 1891: the last time the Reading Room was decorated. During the 1896-7 fever epidemic, the hut would have provided warmth, relative isolation and healthy sea air.

The hut was replaced in 1906 by a new village Reading Room in the front part of the new school on Meadow Lane. It was paid for by the Craster family, in memory of the late Mr Edmund Craster, and officially opened on November 11th that year.[xii] Two years later, the Berwick Advertiser reported that the Reading Room membership was 42, ‘both ladies and gentlemen’, and – tellingly – that ‘It was decided to join the Northern Union of Mechanics’ Institutes’.[xiii] In practice, women did not seem to use the Reading Room. Fishermen born before World War I recalled congregating there in the evenings between the Wars, to play billiards, dominoes and cards, and to read newspapers by oil lamp around the fire in an entirely masculine environment.

The ‘old’ Reading Room was probably given to the fishermen in 1906 by the Crasters, then landlords at the Haven and Square. The years leading up to World War I were particularly difficult in small fishing villages like Beadnell, which struggled to cope with the collapse of the herring industry, the introduction of big steam drifters, and falling white fish catches on the long lines. Several families left Beadnell around this time, heading south to the better prospects of the industrial colliery settlements of Amble, Blyth and Tyneside. Those who stayed hauled up their old herring drifters, some turning them into huts like those which can still be seen on Holy Island. A couple of upturned boats joined the various fishermen’s huts, wash-houses, stables, haylofts and the old Reading Room at Beadnell Haven.[xiv]

From then on, for roughly a century, the Reading Room was used by the Douglas family as a place to make and mend gear. For the first half-century, long lines were baited at a table under the east window in winter. Lines were an ancient form of fishing, dating back to the medieval period in Beadnell.[xv] In more recent times they were normally baited in back kitchens by the womenfolk, but the imbalance of men to women in the Douglas family meant that, in the first half of the 20th century, the men often baited their own lines. The Reading Room was also used for making and mending creeves, storing nets, and the myriad other tasks of fishing life, from tying hooks to ‘sneeds’ (snoods) and stretching ‘tows’ (ropes), to mixing paint and making ‘flaggy bows’ (buoys) for potting and salmon netting. It was usually stacked inside with fleets of creeves and ‘fakes’ (bundled coils) of tows. At the same time, it continued to serve its original purpose as a place for the village men to meet and share news and stories. Whenever fishermen were at work there, others would call in to sit around the stove and chat.

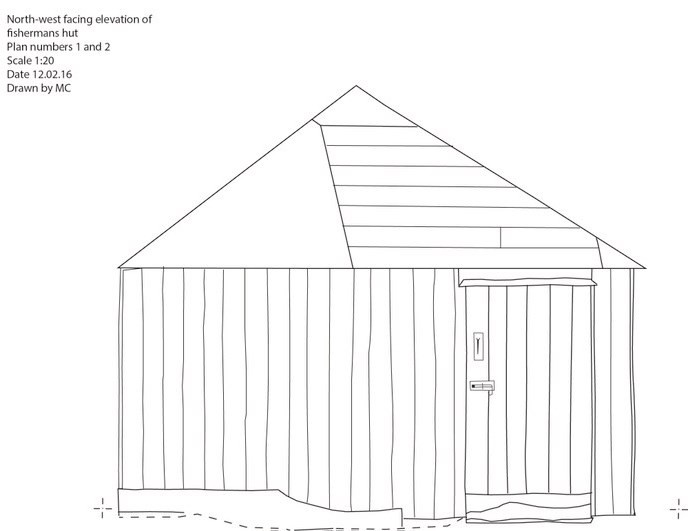

The Reading Room had many characteristic features. Externally it was covered in tar, which made it weatherproof. Tar was used extensively in fishing villages to preserve ropes. A few metres to the north of the Reading Room door lay one of the village wells, and between it and the Haven stood a row of bark-pots, some of which were used to boil tar.[xvi] The tar itself was brought from nearby gasworks, notably at Bamburgh. The fishing economy recycled its materials. Beneath its sealing layers of tar the hut’s wooden roof was neatly covered with old canvas sails. Repairs were made using square-sided blacksmith’s boat-nails. The door was painted marine blue, the traditional colour used for cobles.

Inside, the Reading Room consisted of one large room with a wooden floor, a wooden net-loft extending about three quarters of the length of the roof, a wood-burning stove (originally central, later moved towards the east), tongue-and-groove wainscotting half way up the walls, and a set of shelves and cabinets – presumably originally bookcases – on its southern wall. Two windows looked out to sea on the east side. On the roadside, a pair of windows were permanently shuttered. It was said that the door to the Reading Room had originally been on the west. Fisherman Charlie Douglas (1909-1995) remembered that his father, as a lad, had played a forbidden knocking game involving a button and a string when the hut was still a Reading Room and the door was on the west side. Recent investigations have found no structural evidence for this. The east side of the hut has, however, been replaced at some point. The fishermen recalled that one of the ceiling beams, blacker and harder than the others, had originated in an old smokehouse at the harbour. The panels of the loft were said to be hatches from the holds of 19th century herring keelboats.

The Reading Room contained within its fabric a patchwork of Beadnell’s history. Inside, it smelled of brine and woodsmoke, and its walls were soaked in the stories of a century and a half of seafaring at the Haven, a tradition which stretched back to medieval times. The hut sadly fell out of use in the early 21st century, with the passing of the last of the Douglas fishermen who had kept it in good repair for a century.

Katrina Porteous, 2016

The external details of the Reading Room hut were recorded by CITiZAN (Coastal and Intertidal Zone Archaeological Network) and members of Beadnell Harbour Fishermen’s Association in February 2016. Some additional internal recordings were made by independent archaeologist Harry Beamish and historian Katrina Porteous in March 2016.

References

1. Newcastle Journal, 16.2.1856

2. Shields Daily Gazette, 22.1.1897

3. Porteous, K.; Limekilns and Lobster Pots, Jardine Press 2013, p. 42

4. Porteous, K.; The Bonny Fisher Lad, The People’s History 2003, p. 109

5. Stockdale, Clifton; Mechanics’ Institutes in Northumberland and Durham 1824-1902, unpublished Durham University thesis, 1993, appendix

6. Newcastle Courant, 17.9.1858

7. Berwick Advertiser, 10.12.1858

8. Berwick Advertiser, 10.1.1908

10. Porteous, K.; Limekilns and Lobsterpots, p.36

11. Whellan’s Directory, 1855; Porteous, ibid, p. 66

12. Berwick Advertiser, 29.6.1906

13. Berwick Advertiser, 10.1.1908

14. Porteous, K.; Beadnell – a history in photographs, Northumberland Co. Library 1990, p. 37

15. Osler, A. and Porteous, K., Bednelfysch and Iseland Fish: continuity in the pre-industrial sea fishery of North Northumberland, 1300-1950, Mariner's Mirror vol. 96 no. 1, Feb 2010, pp. 11-25

16. Porteous, K.; Know Your Fishing Heritage: Bark-Pots, Archaeology in Northumberland vol. 17, 2007, pp. 26-27