Saving lives were the Taw and Torridge meet

07/09/2023 | Andy Sherman

On a benign day, at high tide, with a gentle breeze blowing across the estuary the entrance to the River’s Taw and Torridge looks peaceful and far from danger, but at low tide or with a gale force wind roaring up the Bristol Channel this stretch of water becomes deeply treacherous. The winds in Barnstaple Bay can suddenly and unexpectedly change to the northwest, forcing boats onto the shore; and once into the estuary the Bideford Bar, a constantly moving sand bank that stretches across the width of the river can rip the keel out of a ship passing to closely above it.

This narrow, shallow, often changing funnel is the entrance to the Bristol Channel for ships from half a dozen harbours, and during the height of the Victorian period 100’s of vessels would have sailed past Crow Point heading into the Severn Estuary. Regarded by the RNLI as one of the most dangerous stretches of river in the country there were three lifeboat stations positioned around the mouth of the estuary by the middle of the 19th century.

The first lifeboat was introduced to Appledore in February 1825 as a private venture before being taken over by the Devon Humane Society in 1831. At first the lifeboat was stored at the King’s Watch House at Appledore, before being moved to a purpose-built boathouse bigger enough for two lifeboats, located in Watertown on the western edge of the village. The second boat didn’t stay long at Watertown and was moved across to a newly built lifeboat house at Braunton Burrows on the opposite side of the estuary in 1848. By 1855 when the Devon Humane Society was taken over by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution their lifeboats at Appledore and Braunton had helped save the lives of 107 people.

A third lifeboat station was built at Northam Burrows to the west of Appledore in 1851. Overlooking the entrance to the estuary it was surrounded by sand dunes, and had to be rebuilt more than once after being choked by sand. The Northam lifeboat station was difficult to reach and the crew racing out from Appledore would often arrive exhausted and barely able to row effectively. So, the RNLI purchased a horse and cart to ferry the lifeboat crew across the shifting sands.

In 1893 a new lifeboat station was built at Bad Step at the western end of Appledore, where the current lifeboat station stands. A slipway was cut through the rocky shoreline to make launching the boat easier and the Watertown station was closed.

The need for multiple lifeboats is clearly shown in the rescue of the fully rigged ship Penthesilea in 1890. The Penthesilea was sailing between Newport and Mauritius when she was caught in a gale off Appledore and driven onto the shore. As soon as the ship hit the shore a distress signal was lit, which was spotted by the Braunton lighthouse keeper and the watchman at Appledore, who summoned both crews with haste. The Appledore lifeboat launched first, and the crew could see several distressed sailors clambering into the rigging to avoid the raging waves. Unfortunately, the tremendously rough sea prevented them from getting close enough to the ship to rescue the crew, and the lifeboat was soon driven ashore itself with all oars broken. While the Appledore lifeboat struggled against the wind the Braunton Burrows crew had better luck and made it sufficiently close to the tall ship to rescue most of the crew, returning them to shore before setting out again to rescue the remaining sailors (Glasgow Herald, January 2st 1890).

Extraordinarily one of the early 20th century lifeboats from Appledore, the Jane Hannah MacDonald III, survives today. Not only did this lifeboat survive 12 years of service at Appledore saving 23 lives, it was also on station at Eastbourne between 1929 and 1930, and then at Flamborough in Yorkshire from 1933 to 1939. Stationed at Flamborough Head the boat rescued a further three people, but also needed repairs after been holed during a beach launch.

Back in 1910 the lifeboat was delivered to Bideford by train, on a specially converted wagon, before being paraded around the town accompanied by marching bands, Boy Scouts and cheering crowds. The boat was launched into the Torridge on the August bank holiday, after a regatta was held in the ketch's honour and it was followed down the river by a flotilla of other boats to Appledore.

In 1939 the ketch was sold into private hands, renamed the Jane Hanna LN98 and became a fishing boat. Being sold out of the RNLI was not the end of the little boats national service though, as she was called into action during the Second World War. In May 1940 the sailing boat was one of more than 800 vessels that crossed the English Channel heading for Dunkirk to evacuate British and allied troops as part of Operation Dynamo. The former lifeboat was reportedly so full of soldiers at one point during the rescue that seawater poured in through its valves. In June of that year the boat was thought lost at sea, but was recovered of the south coast severely damaged, having had one end completely ripped off.

Having been repaired the boat was sent back to Norfolk to carry on fishing, where its port side was stove in during the catastrophic floods of 1953. Repaired once more the ketch became a pleasure vessel for the next forty years before disappearing into storage in France. Then the Jane Hannah MacDonald III was kindly returned to Appledore where it will become a valued part of the UK’s historic fleet.

While lifeboats were often the last line in defence against losing lives at sea, they weren’t the only measures in place to try and reduce shipwrecks and the loss of life around the estuary.

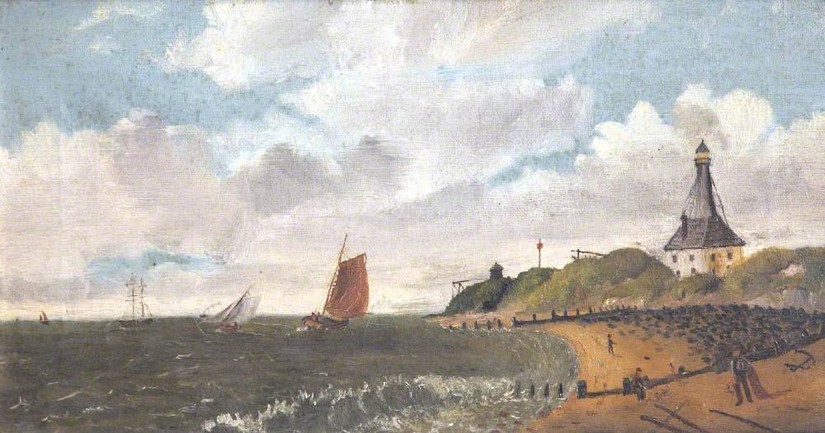

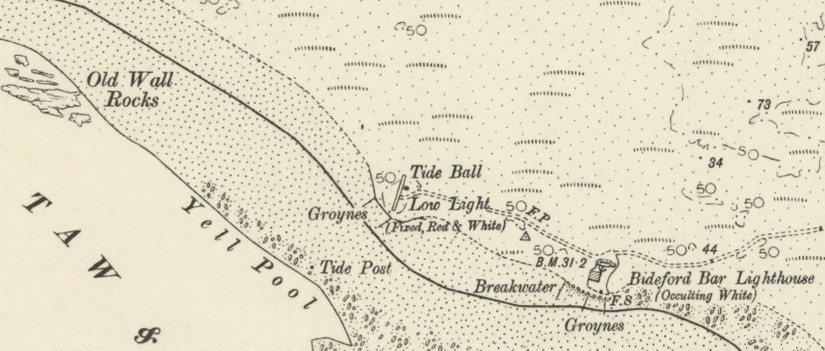

The Braunton Burrows lighthouse or upper light was built at the southern end of the sand dunes and first lit in 1832. It was a substantial building and a cottage for the lighthouse keeper was built next to it. The upper light was paired with the much less substantial, although ingeniously designed low light. The low light consisted of a pair of red and white lights mounted on a rail line, so the structure could be moved backwards and forwards as the sandbar in the estuary moved position. A ship's captain would wait until both lights were in line, which indicated the tide was high enough to cross the sandbar, before entering the estuary.

Both ends of the sandbar and the edges of the deep-water channel through the shallow water were marked by buoys, with Trinity House (the organisation responsible for lighthouses in the UK) keeping a buoy-store on Appledore quay to maintain the markers. Unfortunately, poor weather, inexperience and bad luck meant the lighthouses and buoys didn't always keep sailors out of danger and the lifeboats would spring into action.

A total of 30 medals have been awarded to the brave men and women who crew the Appledore lifeboat with the first awarded in 1829 and the most recent in 2005. The crew have also recieved several forgein awards, having been honoured bu the Spannish Society for Saving the Shipwrecked, and the Emperor of Austria.